Fixed-term employment contracts (such as where a person is employed for, say 6 months) are common in many workplaces.

Understandably, most employers consider they would be protected from an unfair dismissal claim once the term ends.

However, in the case of

Saeid Khayam v Navitas English Pty Ltd t/a Navitas English [2017] FWCFB 5162 the Full Bench of the

Fair Work Commission found that an employee may be able to sue their employer for unfair dismissal even though both the employee and the employer have agreed that the employment will end at the end of the fixed term.

The case highlights the need for employers to keep up-to-date with current workplace laws, and where necessary, to seek legal advice when engaging or terminating employees.

The case

Mr Khayam was employed by Navitas English Pty Ltd ('

Navitas') to perform teaching duties on a series of fixed-term contracts. The last of the fixed-term contracts was for 2 years, and would automatically expire on 30 June 2016, unless terminated earlier by either party with 4 weeks written notice.

An enterprise agreement which applied to Navitas specifically authorised the fixed-term employment of employees and provided Navitas the “absolute discretion” as to whether or not to renew a fixed-term contract, having regard to certain criteria.

On 31 May 2016, Navitas informed Mr Khayam that further employment would not be offered to Mr Khayam based on his performance and disciplinary record. Accordingly, Mr Khayam’s employment ended on 30 June 2016, at the end of the fixed term.

Mr Khayam brought a claim for unfair dismissal against Navitas.

Navitas argued that it had not dismissed Mr Khayam, but rather his contract had simply ended on expiry of the fixed term.

The Fair Work Commission

initially agreed with Navitis.

Mr Khayam appealed the decision of the Commissioner to the Full Bench of the Fair Work Commission.

Termination at the “initiative of the employer”

Establishing that he was dismissed was key to Mr Khayam’s appeal. If Mr Khayam had not been dismissed, he could not maintain his action for unfair dismissal.

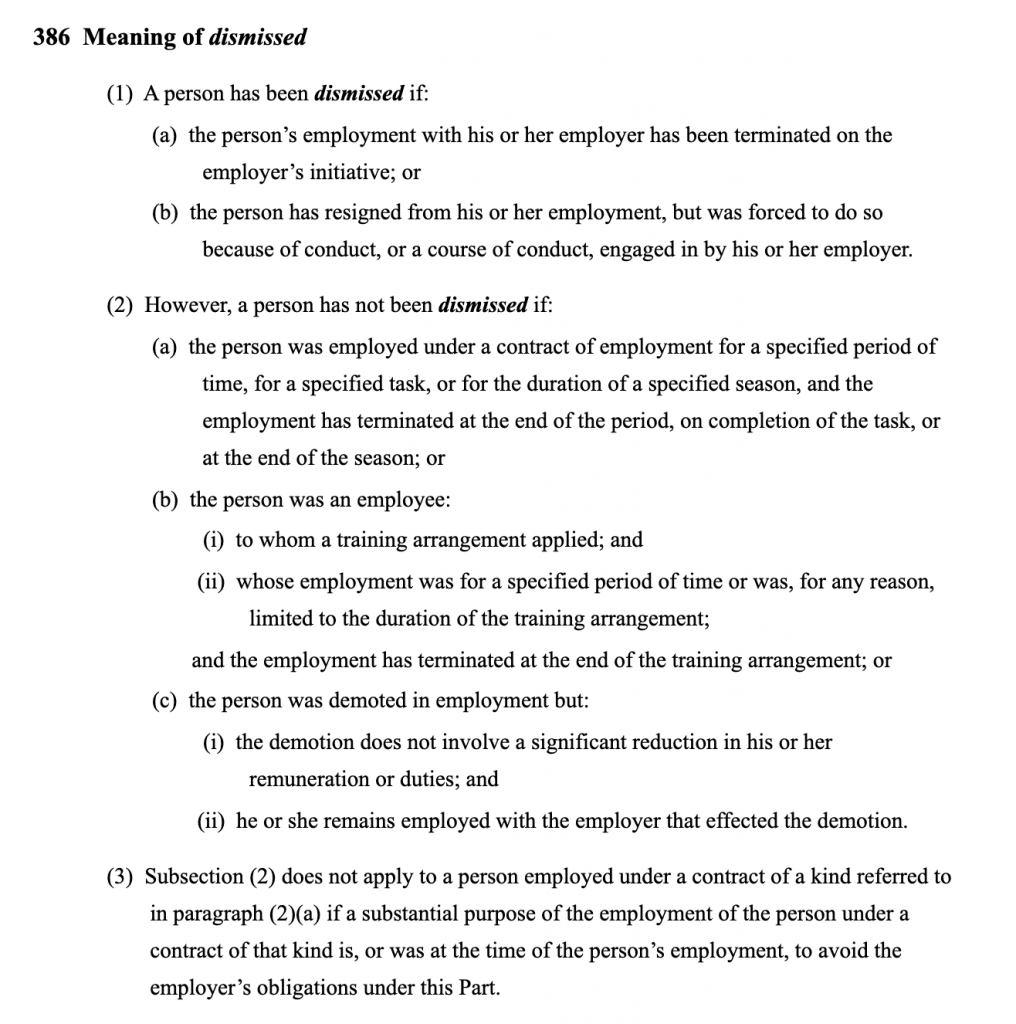

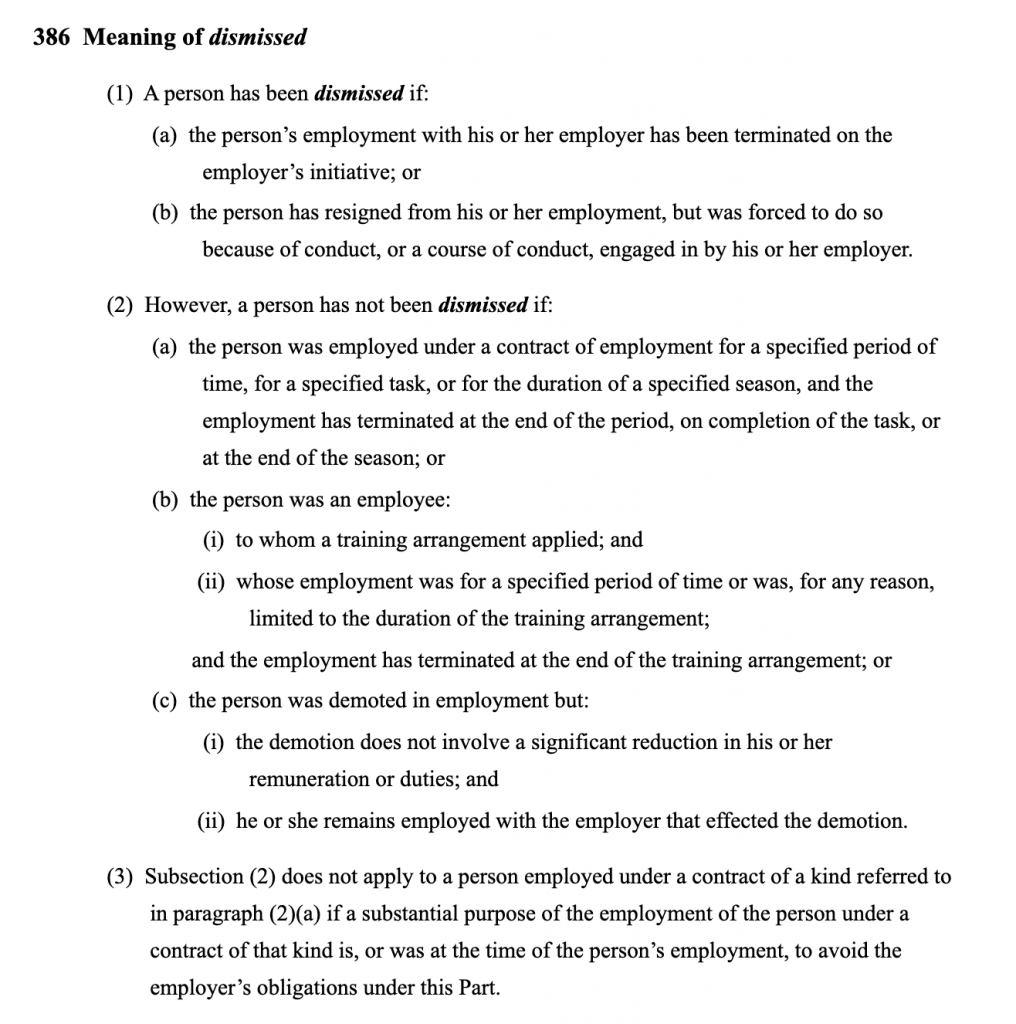

The

Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (the

Act), has this to say:

The Full Bench analysed the relevant cases, and ultimately held (in a split decision) that when considering whether an employee has been dismissed:

- What is important is whether the employment relationship, not simply the employment contract, has been terminated. Where there was a series of short-term employment contracts (as was the case here), the circumstances surrounding the whole employment relationship must be considered, not just the wording of the last employment contract.

- Where the employment is not left voluntarily by the employee, the expression “terminated at the initiative of the employer” requires a consideration of whether an action on the part of the employer resulted in the termination of the employment relationship.

- Even where the parties have agreed to a fixed-term contract and that term has come to an end, the termination of the employment relationship may still be at the initiative of the employer.

- Where there is a genuine fixed-term contract, the termination at the end of the term will generally not be at the initiative of the employer.

The court held that, in many cases, it is necessary to go further than simply considering the terms of the employment contract, for example, where:

- The employment contract is not validly made;

- The employer has misled or misrepresented the true nature of the employment arrangement;

- The employment contract is illegal or contrary to public policy (for example, to avoid the operation of the Fair Work Commission’s unfair dismissal jurisdiction—see s.386(3) of the Act above);

- The employment contract has been varied, replaced or abandoned;

- The employment contract was simply for administrative convenience, and did not represent the true terms of the arrangement between the employer and the employee; or

- An applicable award or enterprise agreement prevents the making of a fixed-term contract.

Interestingly, the Full Bench of the Fair Work Commission said that, because Mr Khayam’s contract stated that either party could terminate the contract upon 4 weeks’ written notice, the employment contract was not for a “specified period of time” and therefore, the exception in section 386(2)(a) did not apply.

The appeal was upheld, and the matter was referred back to the Commissioner to determine whether Mr Khayam has been dismissed under section 386(1)(a).

At the time of writing, the Commissioner has not yet made a determination (or the case settled in the meantime).

However, it is clear that it is open to the Commissioner to decide that Mr Khayam was unfairly dismissed because Navitas had not renewed his fixed-term contract at the end of the term.

Key takeaways

- Employers may not be protected from an unfair dismissal claim once a fixed-term contract ends.

- Employment contracts should be reviewed periodically to ensure they are enforceable.

- Processes should be implemented to manage fixed-term employees to limit exposure to an unfair dismissal claim, particularly when determining whether to renew fixed-term contracts.

- Managers and supervisors should ensure that their conduct does not mislead or misrepresent to the employee the true nature of the employment arrangement.

If you or someone you know wants more information or needs help or advice, please

contact us.

The Full Bench analysed the relevant cases, and ultimately held (in a split decision) that when considering whether an employee has been dismissed:

The Full Bench analysed the relevant cases, and ultimately held (in a split decision) that when considering whether an employee has been dismissed: